Oppression is Worse than Slaughter

The True Story of a Russian Muslim Family Who Fled Atheist Rule

Narrated by Hajjah Naziha Adil

Written by Talibah Jilani

This story began more than seventy years ago in a once-beautiful hamlet nestled deep in the heart of Russia. For thirteen centuries, until the advent of Communism, the Muscovite State of Kazan was steeped in Islamic tradition dating back to the time of Prophet Muhammad (s).

As I was told, my grandfather Ali was orphaned as a young boy. A handsome man in his early twenties, when he met my grandmother Aisha, then seventeen years old, he proposed marriage and they soon settled into family life.

As their family grew, my grandfather, a highly-specialized carpenter, came to work exclusively for high-ranking government officials. To ply his craft, he was given a special pass that permitted his travel to any part of the State in search of superior timber. Little did he know how useful this privilege would become years later.

With the strict implementation of Communism, life as it had been known for centuries came to an abrupt end. It was not uncommon to have one’s home or business confiscated by the new regime, usually without notice. As a child I was told many stories of the hardships my mother’s family experienced under those horrid conditions, and of the risks they took to hold on to their Islam.

Communist soldiers entered my grandparent’s home on several occasions, most often to take inventory. Once they came as the family sat for dinner. They entered without invitation, without so much as a knock at the door, and as the family stared in astonishment, cautious not to challenge the act, one man wrote an inventory of dishes, table linens, utensils and cookware as the other stood guard and berated these humble citizens. “This all belongs to the State. If you break any item, you will pay a fine.” They departed as they had entered, unannounced.

Building a social order in which power is not shared and only rulers are authoritative figures, under the new atheist rule religious oppression only accelerated. Civil rights as we know them today were revoked in the name of Communism. Millions of peace loving Muslims, Christians and Jews were exiled to Siberia in the most deplorable conditions. If they did not die from starvation they froze to death. Their corpses were interred haphazardly in mass gravesites.

Millions of peace-loving Muslims

were exiled to Siberia

where they starved

or froze to death.

Kazan Kremlin Qolsharif Mosque

In their attempts to dismantle religion and end worship of God, the Communists began separating children from their families, and placed them in secular boarding schools where they were stripped of surnames and any religious identity. The day came when a brother did not recognize his own sister and children became propaganda tools of the State. Isolated in colonies, childless parents toiled in factories and on endless tracts of communal farms. Seemingly all reasons to live were dictated by the Kremlin.

By 1937 conditions throughout the once great land had become so dismal that my grandparents realized to remain in Kazan or in any part of Russia posed a threat to their very existence. By then the family had grown to five children, with my uncle the oldest at twelve years, and my youngest auntie a newborn of only two months. My mother, Amina, was then a curious two year-old. So desperate were my grandparents to leave Communist Russia that, as there were spies everywhere, they did not tell a soul of their plans. “We are going to run to Sham (Syria),” my grandfather confided in my grandmother.

To disguise their motives and gain time before a search could be launched, the young family would have to leave everything behind and travel inconspicuously, with no luggage and only one change of clothes. My mother and her infant sister were carried on the backs of their parents. Money was carefully hidden in my grandfather’s expertly fashioned walking stick. They offered prayers for a safe hijra (migration) and set out in the dark of night from their ancestral homeland. Everything before them was an unknown, and they placed their trust in Almighty Allah.

Refugees were common in those days and had crafted various escape routes that my grandfather had studied during his travels around the country. A whisper here, a remark there occasionally yielded some vital details that were useful in planning their escape. For six months the family traveled by night on foot, sighting stars and constellations by which to navigate the often treacherous route. During the day they concealed themselves and slept. If conditions permitted, the children collected wood and twigs and my grandmother made tea and cooked the most humble meals over a small, easily extinguishable fire.

My grandmother vividly recounted one place where they stayed, under tent-like trees with tall trunks that were ten armlengths broad and had foliage that draped to the ground, concealing everything inside. The family took refuge in these trees, with my mother, the baby and my grandparents occupying one and my uncles occupying another, about fifty feet away. My mother awoke and my grandparents sent her to play quietly with her brothers. She again became restless and my uncles, wanting to sleep, sent her back to my grandparents. Hours later my grandmother awoke with a start. “Where is Amina?” she cried, awakening my grandfather. “With her brothers,” be answered. Although the rural countryside was completely silent, my grandmother was certain she had heard little Amina crying.

A search of the area revealed the child was missing. Soon after they all heard Amina’s cries as she approached their hideaway, carried by a local shepherd. “Salamu alaykum,” he greeted the startled family. “I found her far from here, crying for her mother,” he said. Straight-forward, he asked if they were running from the Communists. My grandfather gave no reply. “I asked your daughter, ‘Are you hungry? What did you eat today?’ and she answered, ‘Leaves of trees and green grass.’ I then asked her, ‘Where is your family?’ and she said, ‘We’re staying in some trees.’ Only refugees live this way,” the shepherd remarked.

He offered to buy my mother, a practice that had become more common in those days when hijra was not successful, leaving broken, destitute families to their fate with atheist oppressors. Sometimes children were sold or given to families who showed some promise of caring for them. My grandparents thanked the shepherd for recovering their daughter but refused his offer. “How can you survive? You still have far to go,” he balked. My grandfather replied, “I have left behind everything I know and everything I have achieved in this life for only one purpose-to save my family. I will not stand to see them separated.”

Suspect, they departed from that area and arrived at a place in Georgia, near Uzbekistan. One man who appeared as an Imam reported the refugee family to the secret police and my grandfather was arrested and jailed. Not knowing her husband’s fate and left alone to fend for their children, my grandmother prayed for refuge. Seeing her distress, a local person took them in and allowed them to live in his stable. After three months my grandfather was suddenly released from jail and reunited with my grandmother, who had maintained secret contact with him.

They were even more compelled to continue their hijra and began to push harder to cover more ground each night. Leading the family at a brisk pace and with little Amina strapped to his back, my grandfather, braving the countryside without any hint of light, suddenly found himself falling head over heels down a steep precipice. “Aisha, Aisha, stay back!” his cries pierced the night, followed by an eerie silence. My uncles and my grandmother, who carried her baby, made their way down the steep hill to my grandfather, who wept over Amina, who had suffered significant head trauma. She was alive, but went into a deep coma.

Now escape from Russia became a singular focus. “I will not bury any child here,” Ali said, as they pushed ever faster to reach the border. Day and night they tended to my mother as best as they could, praying for Allah’s Mercy, not knowing if she would survive. She ate nothing and while other family members were hungry, they did not stop long enough to buy food and remained always on the move. My mother recovered from the coma after two weeks, just as the end of their hijra approached.

Along the way my father met a man who advised them the Russians were close on their tracks. “You must be swift, lest they catch you!” be said, advising them of the quickest route to a large river whose bank bordered Turkey. The family made its way as if they were wearing wings and soon reached the vast river. But seeing it, fear set in. “How will we cross it?” my grandmother asked. None of them could swim. Undaunted, my grandfather answered, “Bi idhn Allah – by God’s Will.”

He hoisted the baby above his head and beckoned my eldest uncle to do the same with little Amina, my mother. My grandmother and the boys followed him into the river. Miraculously, the untamed cunent became remarkably calm and while all of them varied in height, the river reached to each person’s chest and not an inch above. They each made it across unhindered. As they reached the opposite bank of the river its force once again raged, and not a moment too soon: the pursuing Russians stood gaping on the other side, angrily waving their rifles in the air. The only ·1oss was my grandfather’s hollow walking stick which contained all their savings in gold.

With their only remaining Russian currency my grandfather was able to buy five cups, five spoons and two plates for the family, a purchase that was long remembered. The Turkish governor gave then good-sized plot of land, enough for them build a small house and grow potatoes. Every planting yielded a huge crop and family became moderately prosperous again, between the farming and my grandfather’s skillful carpentry. It was there that my middle uncle died of illness at age sixteen. My mother’s family lived in Turkey for a total of twelve years, during which· regime of Kemal Ataturk became so oppressive that my grandparents once again discussed hijra.

My grandfather saw the the Prophet (s)

in a dream, in which he instructed

my grandfather to “run towards God.”

It was then my grandfather saw the the Prophet (s) in a dream, in which he instructed my grandfather to “run towards God.” In the dream, RasulAllah (s) was rocking a baby’s cradle, meaning to seek a new life through hijra. My grandfather knew this was a sign for them to leave for Damascus. When my mother was seventeen years old, once again her family of mother, father and seven children prepared for a less stringent immigration. In two months they reached the cradle of civilization, “Damasq”, where two of her siblings died within the first year.

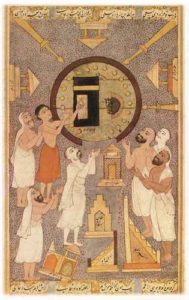

In 1950 my grandfather traveled by camel to Hajj, a journey which took three months.

In 1950 my grandfather traveled by camel to Hajj, a journey which took three months.

Upon his return my grandmother told him, “Read Fatiha. Zaki passed away from illness while you were gone.” So it was, my grandparents lost another child, my nineteen year-old uncle had died. The family stayed in Damascus for many years. When my mother was still quite young Grandshaykh Abdullah ad-Daghestani called her and my father, Shaykh Nazim Adil, who was then a young disciple of Grandshaykh. He said to them, “I have seen it written in the Loh-1-Mahfuz the names ‘Nazim and Amina’, indicating marriage blessed by Heaven.” My parents were engaged and married one month later.

Before his death in 1975, my grandfather helped build Shaykh Abdullah ad-Daghestani’s mosque on Mount Qasiyun. For a emigrant in the Way of God (muhajirah) death, the ritual bath (ghusl), and the grave are always made easy, and in their record it is written that they did hijra for Allah. Those who performed the bath on my grandfather remarked how soft and warm his body was, as if he was asleep.

My father, Shaykh Nazim, often left us for long periods to complete his studies in Istanbul, Cairo, and in Homs. Grandshaykh then instructed my father to return to his countrymen to invite them to Islam. In 1980, our family relocated to Cyprus. My father took up the cause of calling Azan in Arabic five times daily, for which he was jailed for forty days. After patiently completing this duty, he was faced with many opportunities to spread the invitation of Islam in near and far parts of the world.

From the eight children born to my grandparents, five lived to adulthood and produced twenty-five grandchildren. At the time my grandfather died, he knew six great-grandchildren. My grandmother lived out her days in Damascus as a very pious, religious woman. Twice a muhajirah and prepared to meet her Lord, she died in 1989 at the ripe age of eighty years. ◊