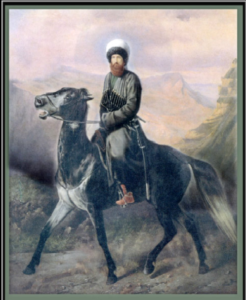

ইমাম শামিল

কেরিম ফেনারি

চেচেন জনগণের স্বাধীনতার জন্য মরিয়া সংগ্রাম অনেক মুসলিমকে অবাক করে দিয়েছে। তিন বছর আগে বসনিয়ার মতো, এই মুসলিম দেশের অস্তিত্ব আমাদের সম্প্রদায়ের অনেকের কাছেই অজানা ছিল। কিন্তু এখন, যখন জার প্রথম বরিসের বর্বর বাহিনী উত্তরের বর্বর ভূমি থেকে চেচেনদের উপর আগুন এবং তরবারি নিয়ে আসছে, তখন মনে রাখা দরকার যে ককেশাস সর্বদা খ্রিস্টান আক্রমণকারীদের কবরস্থান এবং মুসলিম বীরদের জন্মস্থান ছিল যাদের নাম এখনও সেই পাহাড়ি অঞ্চলের সবচেয়ে রোমান্টিক বন এবং উপত্যকায় প্রতিধ্বনিত হয়।.

ককেশাস, যা ইউরোপকে এশিয়া থেকে বিভক্ত করে, পৃথিবীর অন্য কোন পর্বতমালার মতো নয়। ইউরোপের সর্বোচ্চ শৃঙ্গগুলি এখানেই রয়েছে, যার তুলনায় আল্পসকে সবচেয়ে ছোট পাহাড়ের মতো মনে হয়। ক্যাস্পিয়ান থেকে কৃষ্ণ সাগর পর্যন্ত ৬৫০ মাইল বিস্তৃত, তাদের গড় উচ্চতা ১০,০০০ ফুটেরও বেশি। ঢালের উল্লম্ব খাড়াতা এই দর্শনীয় সম্ভাবনাকে আরও ভয়ঙ্কর করে তুলেছে। জর্জিয়ান প্রবাদ অনুসারে, ককেশাস এমন একটি মানুষ যার দেহের কোনও বাঁক নেই, এবং পাঁচ হাজার ফুটেরও বেশি জায়গায় বরফের স্রোতে পড়ে থাকা খাড়া পাহাড়গুলি ভূদৃশ্যকে পাথরের টুকরোয় বিভক্ত করে বলে মনে হয়।.

ককেশাসের দুর্ভেদ্যতা এবং অভ্যন্তরীণ যোগাযোগের অসুবিধার কারণে এখানে অসংখ্য ভিন্ন ভিন্ন মানুষ এবং উপজাতি বসবাস করতে পেরেছে। ঐতিহাসিক প্লিনি আমাদের বলেন যে, যুদ্ধপ্রিয় ককেশীয় গোষ্ঠীগুলির সাথে তাদের আচরণের জন্য রোমানরা একশো চৌত্রিশ জন দোভাষী নিয়োগ করেছিল; অন্যদিকে আরব ঐতিহাসিক আল-আজিজি এই অঞ্চলটিকে ভাষার পর্বত বলে অভিহিত করেছেন, লিপিবদ্ধ করেছেন যে শুধুমাত্র দাগেস্তানেই তিনশো পারস্পরিকভাবে বোধগম্য ভাষা ব্যবহৃত হত।.

কিছু ককেশীয় জনগোষ্ঠী, যেমন ফর্সা চামড়ার চেচেনরা, ইউরোপ থেকে আগত প্রাচীন অভিবাসীদের বংশধর। দাগেস্তানি সহ অন্যান্যদের এশীয় বংশোদ্ভূত বলে মনে করা হয়। কিন্তু কঠোর জলবায়ু এবং অসম্ভব ভূখণ্ড তাদের সকলের উপর একই রকম তপস্বী জীবনধারা চাপিয়ে দিয়েছে। ঝিমঝিম ঢালে সামান্য কৃষিকাজ সম্ভব, এবং শুধুমাত্র সর্বোচ্চ মালভূমিতে ভেড়া পালন করা সম্ভব, যার ফলে কোনও সাফল্য পাওয়া যায় না। ঐতিহ্যগতভাবে, মানুষ আউলস, রুক্ষ ককেশীয় গ্রামে বাস করত, পাথরের ব্লকহাউস এবং খাড়া দেয়াল দিয়ে সুরক্ষিত, যাতে পুমা, নেকড়ে এবং শত্রু উপজাতিরা এড়াতে পারে। সূঁচের মতো পাতলা চূড়ার উপরে সবচেয়ে দুর্গম স্থানে নির্মিত, এই একগুঁয়ে গ্রামগুলিতে যাওয়ার একমাত্র পথ ছিল পায়ে হেঁটে যাওয়া পথগুলির পাশে যা পাহাড়ের মুখের সাথে লেগে ছিল, বিশ্রামের জন্য কোনও জায়গা ছিল না, বরং কেবল আশেপাশের চূড়াগুলির এবং অনেক নীচে ঈগলদের ঘোরাঘুরির দৃশ্য ছিল।.

এইরকম চরম পরিস্থিতিতে, কেবল শক্তিশালী শিশুরাই বেঁচে থাকত। ঢাল বেয়ে উপরে ও নিচে অবিরাম পরিশ্রম করে দিন কাটানোর পর, যখন তারা পরিণত বয়সে পৌঁছাত, তখন চেচেন এবং দাগেস্তানি পুরুষরা ছিল তেজী এবং অত্যন্ত শক্তিশালী। লিপিবদ্ধ আছে যে ঊনবিংশ শতাব্দীর মাঝামাঝি সময়ে কোনও চেচেন মেয়ে কোনও পুরুষকে বিয়ে করতে রাজি হত না যদি না সে কমপক্ষে একজন রাশিয়ানকে হত্যা করত, তেইশ ফুট চওড়া নদীর উপর লাফ দিতে পারত এবং দুই পুরুষের মধ্যে কাঁধের উচ্চতায় আটকে থাকা দড়ির উপর দিয়ে যেত।.

আত্মাদের বিভক্ত করে যে হাই তোলা উপসাগর ছিল তা সহজেই প্রতিদ্বন্দ্বিতা এবং যুদ্ধের দিকে পরিচালিত করত। ককেশীয় জীবন রক্ত-প্রতিহিংসা, কানলি দ্বারা আধিপত্য বিস্তার করত, যা নিশ্চিত করত যে কোনও অন্যায়, যতই সামান্য হোক না কেন, একজন শিকারের আত্মীয়স্বজন প্রতিশোধ ছাড়াই থাকতে পারবে না। চেচেন মহাকাব্য সাহিত্যে শতাব্দীব্যাপী সংঘাতের গল্প প্রচুর পরিমাণে পাওয়া যায় যা একটি মুরগি চুরির মাধ্যমে শুরু হয়েছিল এবং একটি সম্পূর্ণ বংশের মৃত্যুর মাধ্যমে শেষ হয়েছিল। যুদ্ধ অবিরাম চলত, যেমন এর প্রশিক্ষণ ছিল; এবং যুবকরা তাদের ঘোড়সওয়ার, কুস্তি এবং ধারালো শুটিংয়ে নিজেদের গর্বিত করত।.

মুসলমানরা কখনও ককেশাস জয় করতে পারেনি: এমনকি সাহাবারাও, যারা তাদের আগে বাইজেন্টিয়াম এবং পারস্যের সৈন্যবাহিনীকে পরাজিত করেছিলেন, তারাও এই নিষিদ্ধ পাহাড়গুলিতে থেমেছিলেন। শতাব্দীর পর শতাব্দী ধরে, এর লোকেরা তাদের পৌত্তলিক বা খ্রিস্টান বিশ্বাসে বিশ্বাসী ছিল; অন্যদিকে প্রতিবেশী ইরানের মুসলমানরা এটিকে ভয়ের চোখে দেখত, বিশ্বাস করত যে সমস্ত জিনের শাহের রাজধানী ছিল এর তুষারাবৃত চূড়াগুলির মধ্যে।.

কিন্তু যেখানে মুসলিম সেনাবাহিনী প্রবেশ করতে পারছিল না, সেখানে শান্তিপ্রিয় মুসলিম মিশনারিরা ধীরে ধীরে এগিয়ে আসেন। অনেকেই বন্য, ক্রোধী উপজাতিদের হাতে শহীদ হন; কিন্তু ধীরে ধীরে প্রত্যন্ত উপত্যকা এমনকি উচ্চপদস্থ ব্যক্তিরাও ইসলাম গ্রহণ করেন। চেচেন, আভার, সার্কাসিয়ান এবং দাগেস্তানিরা ইসলামে প্রবেশ করে; এবং আঠারো শতকের মধ্যে, কেবল জর্জিয়ান এবং আর্মেনিয়ানরা তখনও ধর্মান্তরিত হয়নি।.

কিন্তু এই বিজয় সত্ত্বেও, দিগন্তে এক নতুন হুমকির আভাস ভেসে উঠছিল। ১৫৫২ সালে, ইভান দ্য টেরিবল উচ্চ ভোলগা নদীর তীরে অবস্থিত মহান মুসলিম শহর কাজান দখল করে ধ্বংস করে দেয়। চার বছর পর রাশিয়ান সৈন্যরা ক্যাস্পিয়ান সাগরে পৌঁছায়। তাদের ভ্যানে বন্য কসাকরা চড়েছিল, নৃশংস ঘোড়সওয়াররা যারা তাদের হাতে পড়া মুসলিম মহিলাদের বন্দী করে জোর করে বিয়ে করে নিজেদের বংশবৃদ্ধি করত। তারা যতই ধর্মপ্রাণ হোক না কেন, তারা প্রথমে একটি দর্শনীয় গির্জা নির্মাণ না করে কখনও নতুন বসতি স্থাপন করেনি, যার ধ্বনি তৃণভূমিতে জারদের সম্প্রসারিত সাম্রাজ্যের উপর বেজে উঠছিল।.

আঠারো শতকের শেষের দিকে ককেশাসের প্রতি খ্রিস্টান হুমকি পাহাড়ি উপজাতিদের নজর এড়াতে পারেনি। তবে, তাদের ঐক্যের অভাব কার্যকর পদক্ষেপ নেওয়া অসম্ভব করে তোলে এবং শীঘ্রই উত্তর চেচেনিয়ার উর্বর নিম্নভূমি এবং (আরও পশ্চিমে) নোগাই তাতার দেশ মুসলিমদের হাত থেকে কেড়ে নেওয়া হয়। যারা মুসলমানরা রয়ে গিয়েছিল তাদের রাশিয়ান প্রভুদের কৃষি দাস হতে বাধ্য করা হয়েছিল। যারা প্রত্যাখ্যান করেছিল বা পালিয়ে গিয়েছিল তাদের শিয়াল-শিকারের অভিজাত রাশিয়ান সংস্করণে শিকার করা হয়েছিল। কিছুকে চামড়া ছাড়ানো হয়েছিল, এবং তাদের চামড়া সামরিক ড্রাম তৈরিতে ব্যবহার করা হয়েছিল। খামারে আটক মহিলাদের প্রায়শই তাদের বাচ্চাদের বাজেয়াপ্ত করতে হত, যাতে বংশধর রাশিয়ান গ্রেহাউন্ড এবং শিকারী কুকুর মানুষের দুধে পুষ্ট হতে পারে।.

এই নীতির তত্ত্বাবধানে ছিলেন সম্রাজ্ঞী ক্যাথেরিন দ্য গ্রেট, যিনি তার প্রেমিকদের মধ্যে সবচেয়ে ছোট, কাউন্ট প্লাটন জুবভকে (তার বয়স পঁচিশ, তার বয়স সত্তর) পাঠিয়েছিলেন তার প্যান-অর্থোডক্স স্বপ্নের প্রথম পর্যায় বাস্তবায়নের জন্য, যার মাধ্যমে খ্রিস্টধর্মের জন্য সমস্ত মুসলিম ভূমি জয় করা হবে। জুবভের সেনাবাহিনী ক্যাস্পিয়ান উপকূলে ভেঙে পড়ে, কিন্তু সতর্কীকরণ ঘোষণা করা হয়েছিল। ককেশাস তার অভ্যন্তরীণ দ্বন্দ্ব থেকে মুখ তুলে তাকিয়েছিল এবং জানত যে তাদের একজন শত্রু আছে।.

বিপদের প্রথম সুসংগত প্রতিক্রিয়া এসেছিল এমন একজন ব্যক্তির কাছ থেকে যার অস্পষ্ট কিন্তু রোমান্টিক ইতিহাস ককেশাসের খুবই সাধারণ। তিনি কেবল এলিশা মনসুর নামে পরিচিত, একজন ইতালীয় জেসুইট পুরোহিত যিনি আনাতোলিয়ার গ্রীকদের ক্যাথলিক ধর্মে ধর্মান্তরিত করার জন্য প্রেরণ করেছিলেন। পোপের ক্রোধের মুখে, তিনি শীঘ্রই উৎসাহের সাথে ইসলামে ধর্মান্তরিত হন এবং রাশিয়ানদের বিরুদ্ধে ককেশীয় প্রতিরোধ সংগঠিত করার জন্য অটোমান সুলতান তাকে প্রেরণ করেন। কিন্তু ১৭৯১ সালে তাতার-তুবের যুদ্ধে তার প্রতিরোধ অকালমৃত্যুতে পরিণত হয়; এবং শত্রুদের হাতে বন্দী হয়ে তিনি তার বাকি জীবন শ্বেত সাগরের একটি হিমায়িত মঠে বন্দী হিসেবে কাটিয়েছিলেন, যেখানে সন্ন্যাসীরা তাকে খ্রিস্টীয় ধর্মে ফিরিয়ে আনতে ব্যর্থ হয়েছিলেন।.

মনসুর ব্যর্থ হয়েছিলেন, কিন্তু ককেশীয়রা সিংহের মতো লড়াই করেছিলেন। তিনি যে প্রতিরোধের শিখা জ্বালিয়েছিলেন তা শীঘ্রই ছড়িয়ে পড়ে, একজন প্রতিভাবান ব্যক্তি: মোল্লা মুহাম্মদ ইয়ারাঘলি দ্বারা লালিত এবং প্রজ্বলিত হয়। ইয়ারাঘলি ছিলেন একজন পণ্ডিত এবং সুফি, আরবি গ্রন্থে গভীরভাবে জ্ঞানী, যিনি কঠোর পর্বতারোহীদের কাছে নকশবন্দী পথ প্রচার করেছিলেন। যদিও তিনি হাজার হাজার মানুষকে ধর্মান্তরিত করেছিলেন, তার প্রধান ছাত্র ছিলেন গাজী মোল্লা, যিনি দাগেস্তানের আভার জনগণের একজন ধর্মীয় ছাত্র ছিলেন, যিনি ১৮২৭ সালে নিজের ধর্মপ্রচার শুরু করেছিলেন, ঘিমরির বৃহৎ আত্মাকে তার কার্যকলাপের কেন্দ্র হিসেবে বেছে নিয়েছিলেন।.

পরবর্তী দুই বছর গাজী মোল্লা তার বাণী প্রচার করেছিলেন। তিনি তাদের বলেছিলেন যে ককেশীয়রা পুরোপুরি ইসলাম গ্রহণ করেনি। তাদের পুরানো প্রচলিত আইন, "“আদত“"যা গোত্র থেকে গোত্রে ভিন্ন ছিল, তার পরিবর্তে শরিয়া আইন অবশ্যই চালু করতে হবে। বিশেষ করে, কানলি প্রতিহিংসা দমন করতে হবে, এবং সকল অন্যায়ের বিচার একটি উপযুক্ত ইসলামী আদালতের মাধ্যমে ন্যায্যভাবে করতে হবে। পরিশেষে, ককেশীয়দের তাদের বন্য, অস্থির অহংকারকে সংযত করতে হবে এবং আত্মশুদ্ধির কঠিন পথে চলতে হবে। তিনি তাদের বলেছিলেন যে, কেবলমাত্র এই নির্দেশিকা অনুসরণ করেই তারা তাদের প্রাচীন বিভাজন কাটিয়ে উঠতে পারে এবং খ্রিস্টীয় হুমকির বিরুদ্ধে ঐক্যবদ্ধ হতে পারে।.

১৮২৯ সালে, গাজী মোল্লা বিচার করেন যে তাঁর অনুসারীরা এই বার্তাটি যথেষ্ট পরিমাণে আত্মস্থ করেছেন যাতে তারা চূড়ান্ত পর্যায়ের রাজনৈতিক কর্মকাণ্ড শুরু করতে পারেন। তিনি দাগেস্তান জুড়ে ভ্রমণ করেছিলেন, প্রকাশ্যে পাপের বিরুদ্ধে প্রচার করেছিলেন এবং ঐতিহ্যগতভাবে আত্মার কেন্দ্রে সংরক্ষিত মদের বড় বড় পাত্রগুলি নিজের হাতে উল্টে দিয়েছিলেন। একের পর এক জ্বলন্ত বক্তৃতায় তিনি জনগণকে অস্ত্র হাতে নেওয়ার আহ্বান জানান। গাজওয়া: সশস্ত্র প্রতিরোধ: একজন মুসলিম শরিয়া মেনে চলতে পারে, কিন্তু তার সমস্ত দান যাকাত, তার সব নামাজ আর মক্কায় তার সমস্ত তীর্থযাত্রা, ওযু, রাশিয়ান চোখ দেখলেই অর্থহীন। তোমাদের বিয়ে অবৈধ, তোমাদের সন্তানরা জারজ, অথচ তোমাদের দেশে একজনও রাশিয়ান অবশিষ্ট আছে!

তিনি ঘোষণা করলেন, জিহাদের সময় এসেছে। দাগেস্তানের মহান ইসলামী পণ্ডিতরা ঘিমরির মসজিদে সমবেত হন এবং তাকে ইমাম হিসেবে স্বীকৃতি দিয়ে তাদের সমর্থনের প্রতিশ্রুতি দেন।.

ঘিমরির মুরিদরা, তাদের কালো পতাকা দ্বারা অন্যান্য পর্বতারোহীদের থেকে আলাদাভাবে দাঁড়িয়ে ছিল, এবং তাদের পোশাক এবং অস্ত্রগুলিতে সোনা বা রূপার কোনও চিহ্ন ছিল না, গাজী মোল্লার পিছনে মুরিদ যুদ্ধের ধ্বনি উচ্চারণ করে বেরিয়ে পড়েছিল: লা ইলাহা ইল্লাল্লাহ. । তাদের প্রথম লক্ষ্য ছিল আন্দির আত্মা, যে রাশিয়ানদের প্রতি আনুগত্যশীল ছিল; কিন্তু মুরিদরা এতটাই চিত্তাকর্ষক ছিল যে তাদের নীরব সৈন্যদের দেখামাত্রই পূর্বের বিশ্বাসঘাতক গ্রামটি কোনও যুদ্ধ ছাড়াই আত্মসমর্পণ করে। এরপর গাজী মোল্লা রাশিয়ানদের দিকে মনোযোগ দেন।.

এই সময়ে, রাশিয়ানরা এই অঞ্চলে খুব কম সংখ্যক উপনিবেশবাদীকে স্থানান্তরিত করেছিল। উত্তরের সমভূমিতে, গ্রোজনি, খাসাভ-ইয়ুর্ট এবং মোজডোকে বৃহৎ সামরিক ঘাঁটি স্থাপন করা হয়েছিল, কিন্তু অন্যত্র মুসলিমদের দেশ থেকে নির্মূল করার প্রক্রিয়া সবেমাত্র শুরু হয়েছিল। তাই গাজী মোল্লা যখন রাশিয়ান দুর্গ ভেনেজাপনায়া আক্রমণ করেছিলেন তখন তিনি স্থানীয় সমর্থনের উপর নির্ভর করতে পারেন। কামান ছাড়াই, তিনি এটি দখল করতে অক্ষম প্রমাণিত হন; কিন্তু ব্যারন রোজেনের নেতৃত্বে এর রক্ষকরা সাহায্যের জন্য পাঠাতে বাধ্য হন। এটি একটি বৃহৎ ত্রাণ স্তম্ভের আকারে এসেছিল, যারা মনে করেছিল যে তারা মুসলমানদের কাছ থেকে কোনও ভয় পায় না, তাই গ্রোজনির দক্ষিণে অবস্থিত বিশাল বনে তাদের তাড়া করে।.

অন্ধকার জঙ্গলে, মুরিদরা তাদের নিজস্ব মাটিতে লড়াই করছিল। বিশাল বিচ গাছের ডাল থেকে গুলি চালিয়ে, নীচু কিন্তু দিশেহারা রাশিয়ানদের জন্য ফাঁদ এবং গর্ত তৈরি করে, তারা পদ্ধতিগতভাবে শত্রু অফিসারদের তুলে নেয় এবং অনেক বিভ্রান্ত পদাতিক সৈন্যকে ধরে ফেলে। বিশাল বিচ গাছ এবং জটলা পাতার এই গোধূলি জগতে, কাঠের রুশ স্তম্ভ, পুরোহিতদের নেতৃত্বে যারা মূর্তি এবং বিশাল ক্রুশ বহন করে, এবং অফিসারদের জন্য পাঁচ ফুট সামোভার এবং শ্যাম্পেনের বাক্স বহনকারী গরুর গাড়িতে বোঝাই, ধীরে ধীরে ক্ষয়প্রাপ্ত এবং ছড়িয়ে ছিটিয়ে পড়ে। বন থেকে কেবল অবশিষ্টাংশ বেরিয়ে আসে: এবং প্রথম মুজাহিদীন বিজয় অর্জিত হয়েছিল।.

প্রতিশোধের জন্য রুশরা মুসলিম শহর তসৌমকেস্কেন্ট আক্রমণ করে, যা তারা দখল করে এবং ধ্বংস করে দেয়। কিন্তু এই বিজয়ের জন্য তাদের চরম মূল্য দিতে হয়েছিল: অভিযানে চারশো রুশ নিহত হয়েছিল, এবং মাত্র দেড়শো মুরিদ নিহত হয়েছিল। আরও বড় অপমান ছিল সোরিতে, একটি পাহাড়ি গিরিপথ যেখানে চার হাজার রুশ সৈন্যকে তিন দিন ধরে একটি ব্যারিকেড দিয়ে আটকে রাখা হয়েছিল, যা পরে তারা ক্ষুব্ধ হয়ে পড়েছিল, মাত্র দুজন চেচেন স্নাইপার দ্বারা পরিচালিত হয়েছিল।.

ক্ষিপ্ত হয়ে রুশরা নিম্ন চেচেনিয়ায় তাণ্ডব চালায়, ফসল পুড়িয়ে দেয় এবং একষট্টিটি গ্রাম ধ্বংস করে। ধীরে ধীরে, চেচেন এবং দাগেস্তানি মুরিদরা তাদের পিছনের পাহাড়ে পিছু হটে। গাজী মোল্লা এবং তার প্রধান শিষ্য শামিল ঘিমরিতে অবস্থান নেওয়ার সিদ্ধান্ত নেন। তীব্র অবরোধের পর, উভয় পক্ষের অনেক হতাহতের পর, রাশিয়ান সৈন্যরা আওয়াজ তুলে নেয়, যারা গাজী মোল্লাকে মৃতদের মধ্যে দেখতে পায়। তখনও তার নামাজের গালিচায় বসে থাকা ইমাম, অদ্ভুতভাবে, এক হাত তার দাড়িতে রেখেছিলেন এবং অন্য হাত আকাশের দিকে ইশারা করেছিলেন। কিন্তু ইতিমধ্যে, তার ডেপুটি, দুটি পাথরের মিনার রক্ষার জন্য ষাট মুরিদের সাথে লড়াই করে, অজেয় বলে মনে হয়েছিল, যে কোনও রাশিয়ানকে লক্ষ্য করে এগিয়ে যেতেন। অবশেষে, যখন মাত্র দুজন মুরিদ বেঁচে ছিলেন, তখন শামিল আবির্ভূত হন, যুদ্ধে বীরত্বের জন্য একটি খ্যাতি প্রতিষ্ঠা করার জন্য যা সমগ্র মুসলিম ককেশাসে প্রতিধ্বনিত হবে। একজন রাশিয়ান অফিসার ঘটনাটি বর্ণনা করেছেন:

অন্ধকার ছিল: জ্বলন্ত খড়ের আলোয় আমরা ঘরের দরজায় একজন লোককে দাঁড়িয়ে থাকতে দেখলাম, যা আমাদের থেকে অনেক উপরে উঁচু মাটিতে দাঁড়িয়ে ছিল। এই লোকটি, যিনি খুব লম্বা এবং শক্তিশালী ছিলেন, বেশ স্থির হয়ে দাঁড়িয়ে ছিলেন, যেন আমাদের লক্ষ্য করার সময় দিয়েছেন। তারপর, হঠাৎ, একটি বন্য পশুর স্প্রিং দিয়ে, তিনি তার উপর গুলি চালানোর জন্য প্রস্তুত সৈন্যদের মাথার উপর দিয়ে লাফিয়ে পড়েন এবং তাদের পিছনে পড়ে যান, তার বাম হাতে তার তরবারি ঘুরিয়ে, তিনি তাদের তিনজনকে কেটে ফেলেন, কিন্তু চতুর্থটি তাকে বেয়নেট দিয়ে আঘাত করে, ইস্পাতটি তার বুকের গভীরে ঢুকে পড়ে। তার মুখটি এখনও অসাধারণভাবে স্থির ছিল, তিনি বেয়নেটটি ধরেন, এটিকে নিজের মাংস থেকে টেনে বের করেন, লোকটিকে কেটে ফেলেন এবং আরেকটি অতিমানবীয় লাফ দিয়ে, দেয়ালটি পরিষ্কার করে অন্ধকারে অদৃশ্য হয়ে যান। আমরা একেবারে হতবাক হয়ে গেলাম।.

রাশিয়ানরা শামিলের পালানোর দিকে খুব একটা মনোযোগ দেয়নি, তারা আত্মবিশ্বাসী ছিল যে মুরিদ রাজধানী ধ্বংসের মাধ্যমে তারা চূড়ান্ত বিজয় অর্জন করেছে। তারা অনুমান করতে পারেনি যে ত্রিশ বছরের যুদ্ধ, যার মূল্য ছিল পাঁচ লক্ষ রাশিয়ান জীবনের বিনিময়ে, তার হাতে তাদের জন্য অপেক্ষা করছে।.

ঘিমরি থেকে নাটকীয়ভাবে পালানোর পর, আহত শামিল যন্ত্রণাদায়কভাবে দাগেস্তানের হিমবাহ-খচিত উচ্চতায় অবস্থিত একটি কুটির, সাকলিয়ায় পৌঁছান। একজন রাখাল তার স্ত্রী ফাতিমাকে খবর পাঠান, যিনি গোপনে তার কাছে আসেন এবং দীর্ঘ জ্বরের চিকিৎসার জন্য আঠারোটি বেয়নেট এবং তরবারির আঘাত বেঁধে তাকে সেবা করেন। কয়েক মাস পর, শামিল আবার ভ্রমণ করতে সক্ষম হন এবং গাজী মোল্লার উত্তরসূরির মৃত্যুর খবর শুনে মুসলিমরা তাকে আল-ইমাম আল-আজম, সমগ্র ককেশাসের নেতা হিসেবে প্রশংসিত করেন।.

শামিল ১৭৯৬ সালে দক্ষিণ দাগেস্তানের আভার জাতির এক সম্ভ্রান্ত পরিবারে জন্মগ্রহণ করেন। তার বন্ধু গাজী মোল্লার সাথে বেড়ে ওঠার পর, তিনি তার কঠোর শৈশবকে মসজিদ এবং ঘিমরির চারপাশের সরু ছাদের মধ্যে ভাগ করে নেন, যেখানে তিনি তার পরিবারের ভেড়া চরাতেন। প্রায়শই তিনি গ্রামের নীচে পাঁচ হাজার ফুট গভীর অতল গহ্বরের কিনারার দিকে তাকাতেন এবং নীচে বজ্রপাতের মেঘের মধ্যে বিদ্যুৎ চমকাতেন। আরও দূরে, ঢালে, ন্যাপথা আগুনের ভৌতিক আভা দেখা যেত, যেখানে প্রাকৃতিক তেল পাথরের মধ্য দিয়ে বুদবুদ হয়ে উঠেছিল, বছরের পর বছর ধরে জ্বলছিল।.

এই কঠোর পরিবেশ এবং তার সাথে যুক্ত কঠোর ককেশীয় লালন-পালনের ফলে ভবিষ্যতের ইমাম খুব কম পার্থিব আনন্দের সাথে জীবনযাপন করতে অভ্যস্ত হয়েছিলেন। যখন তিনি মাত্র শিশু ছিলেন, তখন তিনি তার বাবাকে মদ্যপান ত্যাগ করতে রাজি করান, যদি তিনি থামেন না, তাহলে নিজের ছুরি দিয়ে আঘাত করবেন বলে হুমকি দিয়ে। একজন তরুণ পণ্ডিত হিসেবে তাঁর জন্য প্রয়োজনীয় কঠিন আধ্যাত্মিক শৃঙ্খলা স্বাভাবিকভাবেই এসেছিল বলে মনে হয়েছিল, এবং বিশের দশকের গোড়ার দিকে তিনি ককেশাসবাসীর সম্মানিত সমস্ত গুণাবলীর জন্য বিখ্যাত হয়েছিলেন: যুদ্ধে সাহস, আরবি ভাষায় দক্ষতা, তাফসির এবং ফিকহ, এবং একটি আধ্যাত্মিক আভিজাত্য যা তার সাথে দেখা সকলের উপর গভীর ছাপ ফেলেছিল।.

গাজী মোল্লার সাথে একসাথে, তিনি মুহাম্মদ ইয়ারাঘলির শিষ্য হন, যিনি একজন কঠোর রহস্যময় পণ্ডিত ছিলেন যিনি যুবকদের শিক্ষা দিয়েছিলেন যে তাদের নিজস্ব আধ্যাত্মিক পবিত্রতা যথেষ্ট নয়: তাদের অবশ্যই আল্লাহর আইনকে সর্বোচ্চ করার জন্য লড়াই করতে হবে। শরিয়াকে ককেশীয় উপজাতিদের পৌত্তলিক আইন প্রতিস্থাপন করতে হবে। কেবলমাত্র তখনই আল্লাহ তাদের রাশিয়ান সেনাবাহিনীর উপর বিজয় দান করবেন।.

ইমাম হিসেবে শামিলের প্রথম কৃতিত্ব ছিল সম্পূর্ণরূপে প্রতিরক্ষামূলক। জেনারেল ফেসের নেতৃত্বে রাশিয়ানরা মধ্য দাগেস্তানে একটি নতুন আক্রমণ শুরু করেছিল। এখানে, আশিলতার আত্মায়, রাশিয়ানরা এগিয়ে আসার সাথে সাথে, দুই হাজার মুরিদ কুরআনকে মৃত্যুর মুখোমুখি করে রক্ষা করার জন্য শপথ নিয়েছিল। রাস্তায় এক তিক্ত হাতে-হাতে লড়াইয়ের পর, রাশিয়ানরা শহরটি দখল করে ধ্বংস করে, কোনও বন্দীকে রাখেনি। একটি দীর্ঘ এবং তিক্ত যুদ্ধের জন্য মঞ্চ তৈরি হয়েছিল।.

ইউরোপীয়দের সাথে যুদ্ধের সাথে শামিলের কোন অপরিচিত সম্পর্ক ছিল না। ১৮২৮ সালে হজ্জ পালনের সময়, তিনি ফরাসিদের বিরুদ্ধে আলজেরীয় প্রতিরোধের বীর নেতা আমির আব্দুল কাদেরের সাথে দেখা করেছিলেন, যিনি গেরিলা যুদ্ধ সম্পর্কে তার মতামত তার সাথে ভাগ করে নিয়েছিলেন। যদিও তারা একে অপরের থেকে তিন হাজার মাইল দূরে যুদ্ধ করছিলেন, তাদের পণ্ডিতিগত আগ্রহ এবং যুদ্ধের পদ্ধতি উভয় ক্ষেত্রেই তাদের মধ্যে খুব মিল ছিল। উভয়েই বুঝতে পেরেছিলেন যে বিশাল এবং সুসজ্জিত ইউরোপীয় সেনাবাহিনীর বিরুদ্ধে তীব্র যুদ্ধে জয়লাভ করা অসম্ভব, এবং শত্রুকে বিভক্ত করার এবং তাকে দূরবর্তী পাহাড় ও বনে প্রলুব্ধ করার জন্য অত্যাধুনিক কৌশলের প্রয়োজনীয়তা, যেখানে দ্রুত, অধরা গেরিলা আক্রমণের মাধ্যমে প্রেরণ করা হবে।.

ককেশাসে শামিলের অবস্থানের দুর্বলতা ছিল আত্মাদের রক্ষা করার তার প্রয়োজন। তার সৈন্যরা, বিদ্যুৎ গতিতে এগিয়ে, সর্বদা শত্রুকে এড়িয়ে যেতে পারত, অথবা পেছন থেকে তাকে আকস্মিক আঘাত করতে পারত। কিন্তু গ্রামগুলি, তাদের দুর্গ থাকা সত্ত্বেও, আধুনিক কামান সহ রাশিয়ান অবরোধ পদ্ধতির জন্য ঝুঁকিপূর্ণ ছিল।.

১৮৩৯ সালে, আখুলগোর আত্মায়, শামিল এই শিক্ষাটি শিখেছিলেন। তিন দিকে গিরিখাত দ্বারা সুরক্ষিত এই পাহাড়ি দুর্গটি নিজেই কাঠের তক্তা দিয়ে তৈরি সত্তর ফুট লম্বা সেতু দ্বারা বিস্তৃত একটি ভয়ঙ্কর খাদ দ্বারা দুই ভাগে বিভক্ত ছিল। আখুলগো ইতিমধ্যেই রাশিয়ানদের অগ্রযাত্রা থেকে পালিয়ে আসা শরণার্থীদের দ্বারা পূর্ণ হয়ে গিয়েছিল, এবং এত মহিলা এবং শিশুদের খাবারের জন্য উপস্থিতি দীর্ঘ অবরোধের সম্ভাবনাকে কুৎসিত করে তুলেছিল। কিন্তু তিনি আর পিছু হটতে চাননি: এখানেই তিনি তার অবস্থান তুলে ধরেন।.

এই সময়ের মধ্যে, নকশবন্দী সেনাবাহিনীর সংখ্যা ছিল প্রায় ছয় হাজার, পাঁচশো সৈন্যের ইউনিটে বিভক্ত, প্রত্যেকের নেতৃত্বে একজন নায়েব (ডেপুটি)। এই নায়েবরা, যারা কঠোর এবং পাণ্ডিত্যপূর্ণ, রাশিয়ানদের কাছে এক রহস্য ছিল। ত্রিশ বছরের ককেশীয় যুদ্ধে, একজনকেও জীবিত ধরা যায়নি। আখুলগোতে, এই লোকেরা যথাসাধ্য বসতিটি সুরক্ষিত করেছিল এবং তারপর, সূর্যাস্তের নামাজের পরে সন্ধ্যায়, ছাদে গিয়ে শামিলের জাবুর গাইত, যা তিনি আগে পরিচিত তুচ্ছ মদ্যপানের গানগুলিকে প্রতিস্থাপন করার জন্য রচনা করেছিলেন। আরও অনেক স্তোত্রও ছিল; রাশিয়ানদের কাছে সবচেয়ে পরিচিত ছিল মৃত্যুর গান, যখন রাশিয়ানদের বিজয় আসন্ন বলে মনে হত এবং চেচেনরা একে অপরের সাথে নিজেদের বেঁধে শেষ পর্যন্ত লড়াই করার জন্য প্রস্তুত হত।.

২৯শে জুন রাশিয়ান আক্রমণ শুরু হয়। রাশিয়ানরা পাহাড় বেয়ে ওঠার চেষ্টা করে এবং মুজাহিদিনদের হাতে তিনশো পঞ্চাশ জন সৈন্য নিহত হয়, যারা তাদের উপর পাথর এবং জ্বলন্ত কাঠ ছুঁড়ে মারে। ধমক খেয়ে, রাশিয়ানরা চার দিনের জন্য পিছু হটে, যতক্ষণ না তারা নিরাপদ দূরত্ব থেকে দেয়ালগুলিতে বোমাবর্ষণ করার জন্য তাদের কামান স্থাপন করতে পারে। কিন্তু যদিও দেয়ালগুলি ধ্বংসস্তূপে পরিণত হয়েছিল, তবুও রাশিয়ানরা যতবার আক্রমণ করেছিল, মুরিদরা আউলের ধ্বংসাবশেষ থেকে বেরিয়ে এসে তাদের ব্যাপক হতাহতের সাথে পিছনে ফেলে দেয়।.

Conditions in the village, however, were becoming desperate. Many had died, and their bodies were rotting under the summer sun, spreading a pestilential stench. Food supplies were almost exhausted. Hearing this news from a spy, the Russian general, Count Glasse, decided on an all out assault. Three columns he directed to attack simultaneously, thereby dividing the defenders fire.

The first column, carrying scaling ladders, climbed a cliff on one side of a ravine. But from the apparently bare rocks on the opposing cliff, gunfire directed by Chechen sharpshooters decimated their ranks within minutes. The officers were soon all killed, and the six hundred men, their backs against the cliff, were left trapped by the Murids in the knowledge that exhaustion and exposure would finish them off before dawn.

The second column attempted to make its way to the aoul along the ravine floor. This too ended in disaster, as the defenders rolled down boulders upon them, so that only a few dozen returned. The third column, inching along a precipice, found itself attacked by hundreds of women and children who had been hidden in caves for safety. The women cut their way through the Russian ranks, while their children, daggers in both hands, ran under the Russians and slashed at them from beneath. Here, as always in Chechenya, the women fought desperately, knowing that they had even more to lose than the men. Under this screaming and bloody onslaught, the Russian column staggered and fell back.

Baffled, Count Glasse sent a messenger to Shamyl to arrange a parley. Conditions at the aoul were extreme, and Shamyl, with a heavy heart, struck a deal, agreeing to release his eight-year old son Jamal al-Din as a hostage, on condition that the Russian army departed and left the aoul in peace. But no sooner had the boy been put on the road to St Petersburg than the artillery barrage opened up again, and Akhulgo was once more pounded from every side. Shamyl realised that he had been duped.

The next day, the Russians advanced again on Akhulgo, and found it populated only ravens greedily feeding on corpses. The survivors had slipped away during the night. The only Muslims to remain, those too weak to withdraw, were discovered hiding in the caverns in the nearby cliffs, which were reached with the utmost difficulty. A Russian officer later recorded this as follows:

We had to lower soldiers by means of ropes. Our troops were almost overcome by the stench of the numberless corpses. In the chasm between the two Akhulgos, the guard had to be changed every few hours. More than a thousand bodies were counted; large numbers were swept downstream, or lay bloated on the rocks. Nine hundred prisoners were taken alive, mostly women, children and old men; but, in spite of their wounds and exhaustion, even these did not surrender easily. Some gathered up their last force, and snatched the bayonets from their guards. The weeping and wailing of the few children left alive, and the sufferings of the wounded and dying, completed the tragic scene.

Shamyl had made a desperate attempt to lead his family and disciples away during the night. His wife Fatima was eight months pregnant, and his second wife Jawhara was carrying her two month- old baby Said. But together they managed to inch along a precipice unknown to the Russians, until they reached the torrent below. Here, the Imam brought a tree down to form a makeshift bridge. Fatima crossed safely with her younger son Ghazi Muhammad; but Jawhara was spotted by a Russian sharpshooter, who killed her with a single bullet, sending her and her child toppling over to vanish into the raging torrent. Slowly, Shamyl, his depleted family, and the surviving Mujahideen, dodged the Russian patrols, who were now being aided by the Ghimrians who had gone over to the Russian side. Once they encountered a Russian platoon, and in the ensuing fight the young Ghazi Muhammad received a bayonet wound. But Shamyl’s sword accounted for the Russian officer, whose men fled in terror. They were free again: as at Ghimri, the Imam had effected a miraculous escape.

Count Grabbes report described the capture of Akhulgo in glowing terms. The Murid sect, he wrote, has fallen with all its followers and adherents. The Tsar was delighted; but again, the Russian celebrations were premature. While Shamyl was free he was undefeated. And Moscow had once again given the Caucasus reason to seek freedom.

In 1840, Shamyl raised a new army, and again unfurled his black banners. With the Russians falling back along the Black Sea coast in the face of a Circassian uprising, conditions were right for a major campaign, and by the end of the year, the Imam had retaken Akhulgo, and led his forces onto the plains of Lower Chechenya, capturing fort after fort. The Russian response was chaotic: one sortie led by Grabbe resulted in the death of over two thousand Russians. A new commander, the Tsars favourite General Neidhardt, promised to exchange <Shamyl’s head for its weight in gold to anyone who could capture him; but all in vain. Again and again the Imperial legions were drawn into the dark forests, divided, and annihilated.

Shamyl’s techniques, meanwhile, were improving all the time. On one occasion, he attacked a Russian position with ten thousand men, only to reappear less than twenty-four hours later fifty miles away, to attack another outpost: an astonishing feat. One military historian has written: The rapidity of this long march over a mountainous country, the precision of the combined operation, and above all the fact that it was prepared and carried out under the Russians very eyes, entitle Shamyl to rank as something more than a guerilla leader, even of the highest class.

Russia’s next move was a bold attack by ten thousand men on <Shamyl’s new capital of Dargo. The commander, General Vorontsov, drove through Chechenya and Central Daghestan, encountering little resistance, and finding that Shamyl had burnt the aouls rather than allow them to fall into his hands. Confident, and contemptuous of the Asiatic rabble, he decided to lunge through the final ten miles of forest that separated him from Dargo and Shamyl’s warriors. But when the Russians arrived, again to find that Shamyl had fired the aoul, and turned to retrace their steps, disaster overtook them. Shamyl had watched their advance through his telescope, and calmly directed his Murids to take up positions from which to ambush and harry the Russians. Fighting alongside the Muslims were six hundred Russian and Polish deserters, who dismayed the Russian troopers by singing old army songs at night, their mocking voices rising eerily from the hidden depths of the forest.

Shamyl had positioned four cannon slightly above the devastated aoul, and the Russians charged these and took them with little difficulty. But their way back lay through cornfields that concealed dozens of Murids, who stood up to fire, hiding themselves again before the dazed Russians could shoot back. A hundred and eighty-seven men died before the remains of this column rejoined the main army. Not even the bayoneting of the Chechen prisoners could raise Russian spirits after this omen of impending disaster.

The Russians now began to retreat back through the forest. But the woods were now alive with unseen foes. Slippery barricades blocked their way, and forced them to leave the paths, slashing their way towards ambuscades and bloody confusion. Hundreds of Russians died, including two generals. Heavy rain turned the paths to mud, and made rifles useless, so that at times the two sides fought silently with stones and bare hands. To escape the invisible snipers, the terrified Vorontsov himself insisted on being carried inside an iron box on the shoulders of a colonel. Thus trapped, with over two thousand wounded, and with only sixty bullets left apiece, the desperate Russians sent messengers to General Freitag at Grozny, begging for reinforcements.

At this crucial moment, Imam Shamyl received news that his wife Fatima was dying. He immediately gave orders for the continuing of the battle, and left for the day-long journey to the aoul where she lay. After holding her in his arms as she died, he rode back, to discover, to his deep distress, that his men had disobeyed him. Melting away at the sight of Freitags troops, they had allowed Vorontsovs column to limp out of the forest without further loss. Shamyl boiled with fury, and he fiercely denounced those who had shown faintheartedness instead of clinching the victory. But Russia had paid dearly, as the forest soil of Dargo folded around the bodies of three generals, two hundred officers, and almost four thousand infantrymen. Even today, Russian soldiers remember the Dargo catastrophe in a gloomy song: In the heat of noonday, in the vale of Daghestan, With a bullet in my heart, I lie …

For another ten years, Shamyl’s flags flew over Chechenya and Daghestan, proclaiming what Caucasians still refer to as the Time of Sharia. The Tsar, fuming in his vast palace in St Petersburg, received message after courteous message from his generals praising their own victories; yet still Shamyl ruled. Vorontsov, Neidhardt and others were recalled, and died in gilded obscurity. But in 1851, command was given to a younger man, General Beriatinsky, the Muscovy Devil who was to change the course of the war for ever.

The new Russian commander knew his enemy, and adapted his techniques accordingly. He knew that the Chechens disliked going into battle unless they had performed their ওযু-ablutions, so he ensured that great dams were built to cut off the water supply to his opponents. He adopted a policy of bribing villages into accepting Russian authority, and delayed the enserfment process indefinitely. He ended the former policy of informally butchering women and children during the capture of aouls. But his most significant innovation was his long, slow campaign against the forests. Like the Americans in Vietnam and the French in Algeria, he realised that his enemy could only be defeated on open ground. He thus deputed a hundred thousand men to cut down the great beech trees of the region. Some were so vast that axes were inadequate, and explosives had to be used instead. But slowly, the forests of Chechenya and Daghestan disappeared; while Shamyl, watching from the heights, could do nothing to bring them back.

In 1858, the last great battle erupted. The Ingush people, driven from their aouls by the Russians into camps around the garrison town of Nazran, revolted, and called on Shamyl for aid. He rode down from the mountains with his mujahideen, but sustained a crippling defeat under the cannon of a relief column sent to support the beleaguered garrison. When he returned to the mountains, he found the support of his people beginning to melt away. Whole aouls went over to the Russians rather than submit to siege and inevitable destruction. Even some of his most faithful lieutenants deserted him, and guided Russian troops to attack his few remaining redoubts.

In June 1859, Shamyl retreated to the most inaccessible aoul of all: Gounib. Here, with three hundred devoted Murids, he determined to make a last stand. The Russians were driven back time and again; but finally, after praying at length, and moved by Beriatinskys threat to slaughter his entire family if he was not captured alive, he agreed to lay down his arms.

Thus ended the Time of Sharia in the Caucasus. The Imam was transported north to meet the Tsar, and then banished to a small town near Moscow. Here he dwelt, with a diminishing band of family and relations, until 1869, when the Tsar allowed him to leave and live in retirement in the Holy Cities. His last voyage, through Turkey and the Middle East, was tumultuous, as vast crowds turned out to cheer the Imam whose name had become a legend throughout the lands of Islam.

His son Ghazi Muhammad, released from Russian captivity in 1871, travelled to meet him at Makka. He arrived, however, when the Imam was away on a visit to Madina. As he was walking around the Holy Kaba, a tattered, green-turbaned man came up and suddenly cried, “O believers, pray now for the great soul of the Imam Shamyl!”

It was true: on that same day, Shamyl, murmuring “Allah! Allah!,” had passed on to eternal life in Paradise. He was buried, amid great throngs and much emotion, in the Baqi Cemetery. But his name lives still; and even today, in the homes of his descendents in Istanbul and Madina, in flats whose walls are still adorned with the faded banners of black, mothers sing to their children words which will be remembered for as long as Muslims live in Chechenya and Daghestan: